A sailing adventure among the stunning islands of Palawan.

The Philippine island province of Palawan offers gorgeous beaches, aquamarine waters and secluded coves. Now, an ethical boat tour meanders wherever passengers choose to go, and offers a close-up of village life on the water’s edge

The endless ocean, broken occasionally by sand-fringed islands, stretched before me. A salty breeze caressed my face and two magnificent sails billowed bright in the sunlight as we headed into the unknown. I was on an oceanic adventure, sailing across the Palawan archipelago in a replica of a boat that first crossed these Philippine seas more than 1,000 years ago.

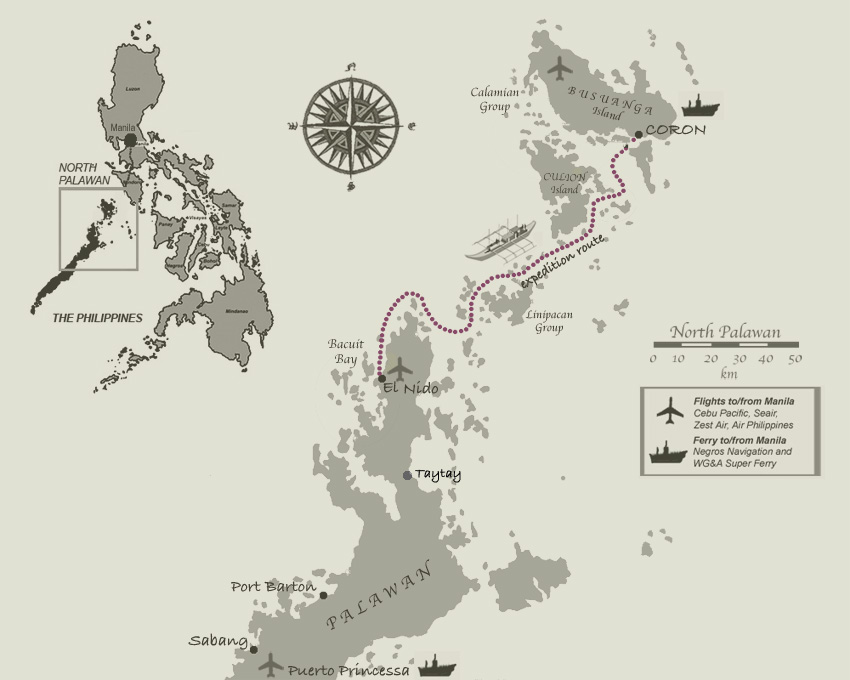

My trip was a new eco sailing expedition by a local company, which offers off-the-beaten-track sailing holidays between El Nido, in the north of long, thin Palawan island, and Coron, further north, off Busuanga island. Taking in areas few tourists visit, it directs some of its profits to funding community projects across the islands.

The newly built boat, christened Balitik (which means “constellation of Orion” in Hiligaynon, a language of the Western Visayas region of the Philippines), was their latest and most ambitious project. We were to spend three days at sea, setting off from Coron and stopping at different islands each night, with only a vague route planned. Most of the journey would depend on the wind, the weather and the whims of the crew and guests. It was a chance to go off-grid and see Palawan’s beauty, untouched by tourism.

The day was perfect as we boarded – cotton puff clouds drifting across the sky, the luminous aquamarine ocean shifting gently. It was difficult to believe that just a year earlier, typhoon Haiyan, one of the strongest storms in recorded history, tore across this region, leaving 8,000 people dead or missing and four million displaced. By the time it hit Palawan, in the south-west Philippines, its force had waned, but small island communities were devastated.

Gradually, people here have been putting their lives back together, with Tao Philippines at the forefront of the mission to deliver aid to the area. Today, there is little evidence of any damage in the region – though thousands are still waiting for new homes in the worst-hit areas, such as Tacloban and Guiuan, in the east of the country.

Balitik was something to behold. At 22 metres long, with room for 20 guests and a crew of nine, it is the largest boat of its kind in the Philippines today, a reconstructed paraw, the traditional Philippine outrigger sailing boat once used to transport cargo and passengers.

I had watched the boat’s development before I saw it in real life, following the trials and tribulations of its birth on a blog. Balitik was much bigger than initially planned, much costlier and much more demanding, but when I first laid eyes on it, I could see why the owners of Tao Philippines – British sailing enthusiast Jack Footit, Eddie Brock, a Filipino who met Footit while waiting tables in Edinburgh, and Gener Paduga, an avid sailor who grew up in Palawan – had put their heart and soul into the project.

Now, three kayaks were shuttling back and forth between the shore and the boat, bringing supplies and guests on to its bobbing deck. A flurry of activity on board signalled our imminent departure, as the crew scuttled into position, gathering up the ropes. Datu, the boat’s jack russell, scampered to attention. Balitik was ready to set sail. I settled in, putting my bags below deck and chatting to Eddie, Gener and Lito, a former smuggler turned boat captain. Gener showed me around the captain’s den, pointing out the old navigation devices, used when sailors relied much more heavily on the constellations.

Aside from modifications to make the boat more reliable and comfortable than its ancient counterpart (including a motor for windless days), a lot of effort had gone into recreating an authentic experience of traditional boat life. Vegetables hung from the roof of the kitchen – originally a measure to stop rats getting to them on long journeys, though thankfully no rats were to be seen, and the crew had brought along a pig, as is the tradition, to eat any leftovers.

Days rolled by at a leisurely pace. I sprawled under the decks’ canopies, mesmerised by the shimmering ocean, and watched occasional passing fishermen making their rounds of pearl farms. As the sun crossed the sky, I too shifted position, finding cosy nooks within the mesh of ropes snaking across the boat. Two nets at the prow soon became my favourite viewing pouch and siesta spot.

Several times a day we’d stop to explore secret snorkelling spots, hidden caves or picture-perfect bays. I donned my snorkel and mask and dived into the cool deep blue, seeking sunken wrecks, stingrays and schools of tropical fish. In the evenings we moored at the islands where they have their base camps. First was Pinagbuyutan, where a dense, knotted jungle crept up to the mangrove-fringed shore. The low hum of crickets, cicadas and lapping waves accompanied me as I strolled at sunset to my hut on the beach.

The paradise landscapes of Cadlao island, with its virgin chalk-white sand backed by limestone cliffs, could indeed have been the inspiration for Alex Garland’s novel The Beach. He was living in the Philippines when he wrote it. Some nights, I basked in the rawness of nature; on others I laughed and played with village children, who would show me their favourite swimming spots or beachcombing treasures. When we docked at one island, a boy ran up to me and ushered me to his hut, where his pig had just given birth. He proudly showed me the heavy mother and her dozens of suckling piglets.

Gener would fish from the back of the boat, and when I wanted to hide from the wind and the sun, I retreated to the kitchen, which was always bustling with activity and smelled strongly of coconut milk or grilled fish. Meals were Filipino food at its most basic and tasty, using ingredients found around us. Stuffed squid marinated delicately in calamansi (a type of lime), curries of vegetables grown in Tao’s organic gardens, grilled grouper fish and banana lotus. Dinner became a theatre of food, and I dug my feet into the sand and sipped rum and pineapple cocktails while colourful fish and squid were brought out to be grilled.

As the days passed I learned more about the scale of the project to recreate a paraw from the crew. Eddie, Jack and Gener had hatched the idea because they wanted to revive the Philippine sailing traditions that had almost died out with the arrival of the motorboat in the 1970s. Only a handful of small traditional sailing boats exist for show, in tourist hotspots such as Boracay.

Finding men to build the boat had been the initial hurdle. There were no blueprints or diagrams. Knowledge of boat-making was passed down from generation to generation, so they searched the Philippines to find three master carpenters who still remembered the traditional structure: Jaime Maltos and Bernando Conche from Palawan, and Celso Conde, a boat builder from the Sulu sea to the east. After two years of research and building (five types of wood were used), they fulfilled their dream and successfully launched the largest paraw in the Philippines.

For the traveller who wants to go where few tourists have gone before, the trip is a dream come true. Traversing these seas by boat is really the only way to explore the remotest islands and discover their rare beauty. And a tour that doesn’t adhere to any particular schedule, that changes and evolves depending on the weather and the whims of its passengers, yet takes care of everything, is hard to find.

The fact that our tourist pesos were helping the people on these islands get back on their feet again allowed us to bask in the glow of doing good, as we soaked up the culture, the food, and the glorious scenery of the open sea.

By Aya Lowe

8th of November

www.guardian.com

#asiatours #toursasia #palawan #coron #elnido #philippinestours #philippines #insighttoasiatours